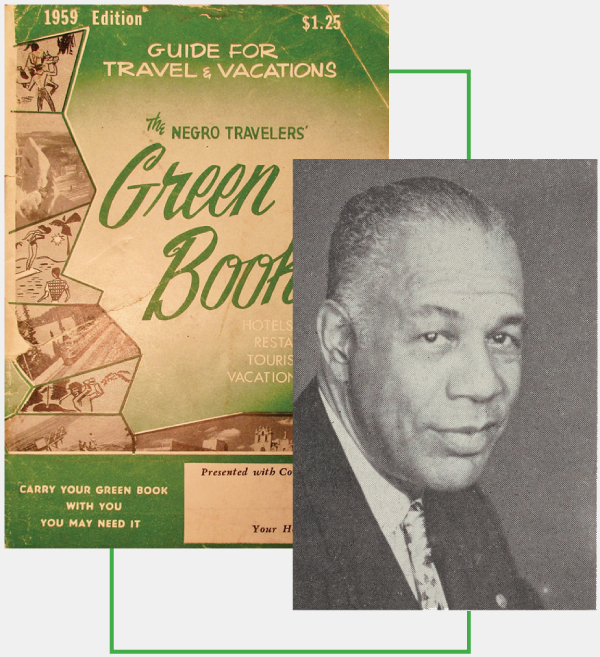

Victor H. Green and the Legacy of The Negro Motorist Green Book

How one man’s guidebook helped Black Americans navigate America’s Jim Crow roads—and continues to inspire today’s global inclusion efforts.

Setting the Scene: Travel in Jim Crow America

In the 1930s, the promise of America’s open road was, for Black travelers, shadowed by the threat of discrimination, harassment, and even violence. Racial segregation laws—known as Jim Crow—varied from state to state, and few businesses welcomed African Americans with open arms. “Sundown towns” barred Black visitors after dark; hotels, restaurants, gas stations, and restrooms often refused them entry. What should have been simple rest stops could become dangerous dead ends.

Enter Victor H. Green (1892–1960)

Victor Hugo Green was born in 1892 in Manhattan, New York City, the son of working-class parents. He served as a postal carrier for the U.S. Postal Service beginning in 1917, a job that kept him on the move throughout New York City’s boroughs and gave him a firsthand understanding of the challenges faced by Black Americans on the road. Around 1934, Green—then living in Harlem—began gathering information on safe lodging, restaurants, and other services that would welcome Black travelers.

The First Green Book: A Practical Roadmap for Safety

In 1936, Green self-published the inaugural edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book, a slim, 15-page booklet listing a few dozen businesses—mostly in New York City—that would serve Black patrons. Priced at 25 cents, it was sold by mail order and at prominent Black-owned establishments in Harlem.

Key features of the early editions included:

- Hotels and Guest Houses that accepted Black guests.

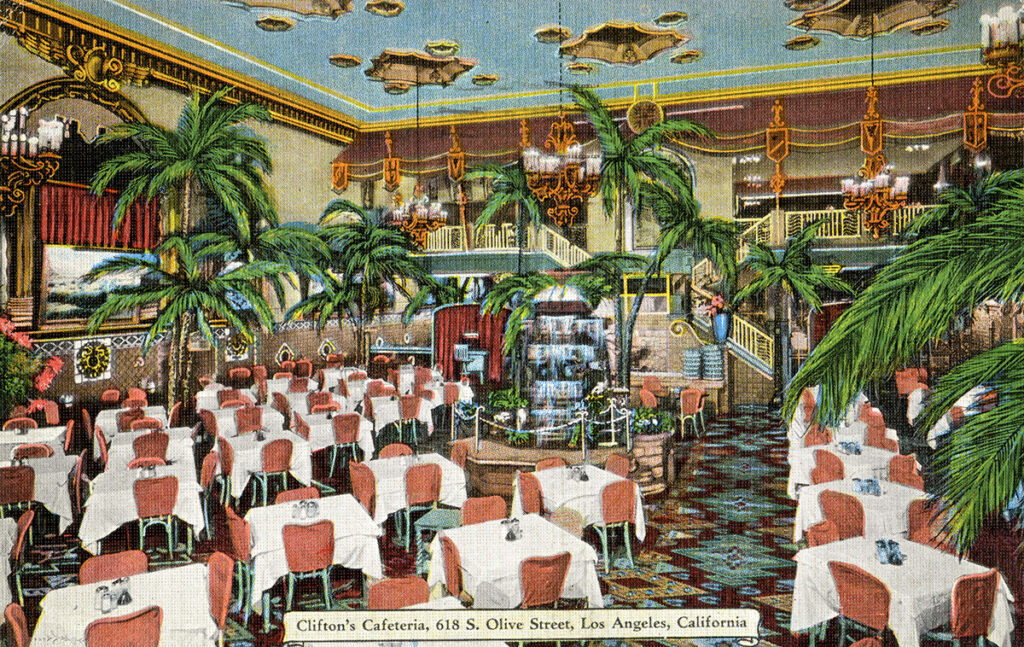

- Restaurants and Cafés offering meals without segregation.

- Service Stations where motorists could refuel and receive automotive help.

- Entertainment Venues, such as theaters and nightclubs.

Green’s motto was simple and hopeful: “Carry your Green Book with you—‘vacation without aggravation.’”

Expansion and National Reach

By 1949, as America’s Black middle class expanded and automobile ownership grew, the Green Book had outgrown its New York origins. Victor H. Green enlisted a series of regional correspondents—postal carriers, business owners, clergy—across every state to submit updates. Each annual edition swelled to hundreds of pages, listing thousands of businesses coast to coast, from Harlem to Los Angeles, Detroit to Miami, Houston to Seattle.

At its height in the mid-1950s, the Green Book offered:

- Detailed street addresses and telephone numbers.

- Symbols denoting women- and veteran-friendly businesses.

- Notes on seasonal operations, wheelchair accessibility, and Spanish-speaking staff.

This remarkable grassroots network turned Victor Green’s guidebook into an essential travel companion, empowering generations of Black families, salesmen, entertainers, and civil rights activists to journey with greater confidence.

Impact Beyond Listings: Community and Resistance

The Green Book was more than a directory; it was an act of quiet resistance. In the face of segregation, it connected Black communities across disparate regions, fostering solidarity and economic support for Black-owned businesses. It also provided a measure of psychological security—knowing that, at each stop, a friendly face and a safe room awaited.

Many Green Book-listed establishments—family motels, boarding houses, cafes—served as informal hubs for organizing civil rights efforts. Employees and proprietors often risked economic retaliation by appearing in the guide, yet their inclusion was a brave affirmation of dignity.

Decline and Rediscovery

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public accommodations, and by the late 1960s the original Green Book was obsolete. Victor H. Green passed away in 1960, never fully seeing the legal end of Jim Crow. His final editions, however, remain treasured historical artifacts—preserved in libraries, museums, and private collections.

For decades the Green Book was little more than a poignant footnote in travel history—until the 21st century, when scholars, filmmakers, and community activists rediscovered its profound cultural significance. Exhibitions at the Schomburg Center in New York and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture have spotlighted Victor Green’s work, and the Oscar-nominated film Green Book (2018) introduced the concept to millions worldwide.

Carrying the Torch: Green Book Global

Today, inspired by Victor H. Green’s pioneering spirit, Green Book Global has emerged as a modern platform dedicated to mapping inclusive, safe, and welcoming destinations for travelers of all backgrounds. Drawing on digital tools—from mobile apps to interactive maps—it continues Green’s legacy of community-sourced recommendations, ensuring that every journey can be one of discovery, respect, and shared humanity.

Victor H. Green’s Green Book remains a testament to the power of practical solidarity and the unyielding quest for safe passage. More than eighty years after its first publication, its guiding principle—“vacation without aggravation”—resonates as strongly as ever, reminding us that true freedom is measured not just in miles traveled, but in the dignity afforded along the way.

Check out our History of African American Hotel Ownership for more information